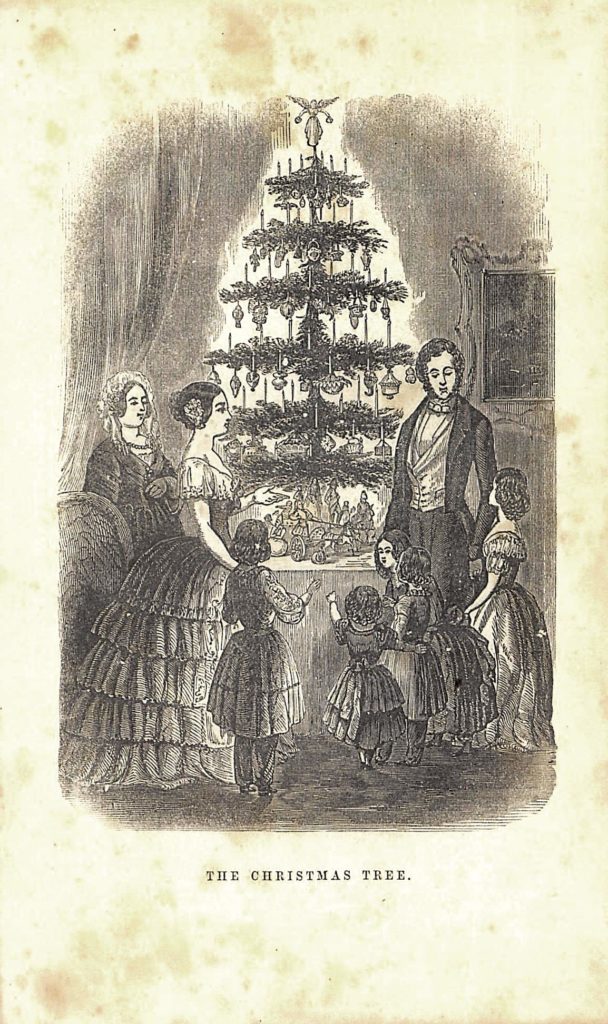

The first time that a Christmas tree was depicted in print in the United States was in the Goudy’s Ladies Book, in 1850.

Interested in looking at more plates from Godey’s Ladies Book? Stop in to the RFL and ask!

Engage, Enrich, Entertain

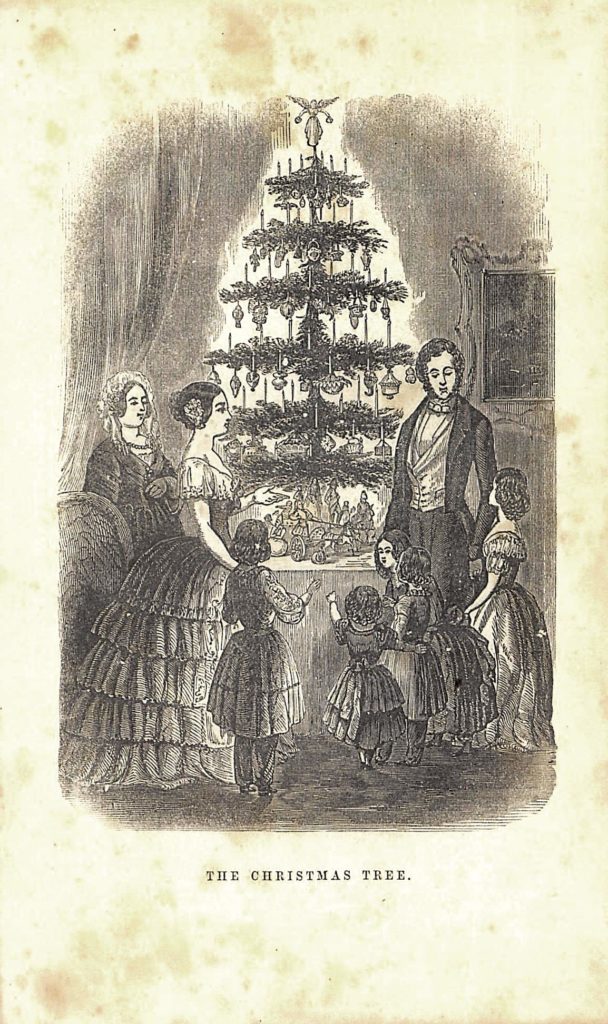

The first time that a Christmas tree was depicted in print in the United States was in the Goudy’s Ladies Book, in 1850.

Interested in looking at more plates from Godey’s Ladies Book? Stop in to the RFL and ask!

By Sarah Hale, 1827

In her 1827 novel Northwood, Sarah Hale explains that the first Thanksgiving was to celebrate the arrival of a ship from England laden with provisions at a time when the early settlers of Boston were nearly out of food. No mention of friendly Indians in this version.

She adds Thanksgiving is not to celebrate that event, but rather “a tribute of gratitude to God, an acknowledgement that God is our Lord, and that as a nation we derive our privileges and blessings from him.” She notes that we have no national religion because “our people do not need compulsion to support the Gospel.”

Hale’s campaign for a national Thanksgiving holiday had begun when she wrote this novel. In Northwood she says that “when Thanksgiving will be celebrated together across the nation it will be a grand spectacle of moral power and human happiness such as the world has never witnessed.”

Regarding charity on the holiday, she mentions that it is an occasion of “good gifts as well as good dinner” and paupers, prisoners, all will be feasted.

In Northwood, a long-absent son and his guest from England arrive unexpectedly the night before Thanksgiving. The family stays up until midnight, talking. The mother gets up the next morning and prepares a sumptuous breakfast for the guests, who are roused at 8. The family eats, and then departs for church, leaving one of the teen-aged daughters to “superintend the various operations of stewing, roasting, baking, etc.” It is unclear who she is superintending. (They have one wretched maid, “shiftless old Hester,” who spends the holiday with her family.)

The family comes home from church to the feast, which we can only assume has been cooked over the preceding days. There is no way the teenager produced this feast while the long sermon was preached. November was colder in 1827, and there must have been ice boxes, so we can hope the lack of refrigeration was not a problem.

The feast is arrayed on a long table in the parlor, covered with a bleached white damask cloth woven by the mother. Everyone, including every child, has a seat at the table.

The menu:

Roast turkey took precedence with savory stuffing and broth.

It was flanked on either side by a leg of pork and a loin of mutton.

There were innumerable bowls of gravy and plates of vegetables.

There was a goose and a pair of ducklings on side stations.

The middle of the table was graced by a chicken pie, wholly formed of the choicest parts of fowls, enriched and seasoned by a profusion of butter and pepper, and covered with puff paste.

There were plates of pickles, preserves, and butter.

A wine glass and two tumblers were at each place, with a slice of wheat bread on top of one of the inverted tumblers.

For dessert there was a huge plum pudding, custards, and pies. Pumpkin pie occupied the most distinguished niche. There were also several kinds of rich cake and a variety of sweetmeats and fruit.

To drink they had currant wine, cider, and ginger beer, all made by themselves. Ms. Hale notes that there were no foreign wines or “ardent” spirits.

After dinner they drank coffee, an innovation added to please the son who was raised in the south.

Ms. Hale emphasizes that all this abundance is “common food,” not foreign or rare luxuries. She says that “excessive luxury and rational liberty are never yet found compatible.” Everything on the table, except salt and a few spices (and I suppose the coffee), was raised or grown on the home farm.

Hale speaks earnestly of the need for simplicity in decoration and attire and the virtues of this county fare. There would have been nothing simple, however, for the housewife who was encouraged to produce such a feast. From the weaving of the damask to the brewing of the beer, it seems an impossibly high bar to reach.

Setting aside the dietary extremes, the mention of avoiding luxury as a prerequisite for our own liberty is worthy of consideration before we throw the holiday of Thanksgiving aside and head for the malls in search of ever more gifts and decorations. We might then more closely approach that grand moral spectacle of human happiness that Hale anticipated.

– Sandra Sonnichsen

by Judith Freeman Clark

Throughout the 19th century, most Americans viewed proponents of equal opportunity for women as lunatics or anarchists bent on destroying polite society. In such a society women were generally tied to domestic responsibilities, and their educational and professional choices were severely limited by virtue of their gender. Happily, some, like New Hampshire’s Sarah Josepha (Buell) Hale, born in Newport in 1788, cherished the opinion that society would be improved, not damaged, by women’s contributions.

Editor of Godey’s Ladys Book from 1837 to 1877, Sarah believed women should seek a more respectable station in social life than merely that of a household drudge or a pretty trifler. Sarah was neither of these things. Her family believed education was important, and although she had no formal schooling, she was tutored by her brother Horatio, a Dartmouth College Student.

Sarah’s first job as a schoolteacher may have been inevitable, but her commitment to educating boys and girls was far from ordinary. Sarah taught reading, mathematics “ even Latin “ with indifference to the fact that her pedagogy was atypical. Unlike most teachers, she allowed each student to proceed at an individual pace instead of requiring group recitation. In addition to being applauded for her instructional methods she became well known for her poems. One became a children’s classic. Mary’s Lamb (better known as Mary Had a Little Lamb) has been memorized, sung, and recited by generations of Americans, but few know that the author was a self-educated village schoolmistress with a penchant for innovative teaching.

Sarah was courted by lawyer David Hale, whom she married in 1813, quitting her school post to do so. Despite the birth of four children, she studied in the evenings and diligently plugged away at her writing. In 1822, when David died of pneumonia, she had published essays, poems, and short stories, and had started a novel. Sarah (who gave birth to her fifth child days after David’s death) knew a teachers pay would be insufficient for her family’s needs, so she opened a millinery business in Newport with her sister-in-law. In the midst of increased business and domestic responsibilities, Sarah continued writing during her spare time.

Within a few years she had published a book of poems and was writing regularly for The American Monthly Magazine, The Minerva, The New York Mirror, The Spectator and the U.S. Literary Gazette. However, the tour de force of Sarah’s literary output was a novel, Northwood, published in 1827. Preceding Uncle Toms Cabin by more than two decades, it introduced a new American genre: novels about slavery. Praised by critics at home and abroad, Northwood became the passport to an editorial career to which Sarah dedicated the next 50 years.

Following Northwoods success Sarah Moved to Boston to become editor of the American Ladies Magazine. There she defined her journalistic mission “ to educated and enlighten readers, not merely entertain them. She did this by presenting, as she stated, whatever is calculated to illustrate and improve the female character. By the time her magazine emerged in 1836 with Louis Godey’s Ladys Book, Sarah had become well known as an editor of perception, discernment, and demanding literary standards.

Over the course of her career her position enabled her to become acquainted with many who devoted themselves to education in all of its forms. These notables included writer Oliver Wendell Holmes, Samuel Gridley Howe, a Harvard professor and founder of the Perkins Institute for the Blind, and musician Lowell Mason, who published many of Sarah’s verses in his songbook the Juvenile Lyre, used in public schools throughout America. Sarah also became a good friend of Emma Willard, founder of a female seminary in Troy, New York.. Its goal – to educate young women as schoolteachers “ was dear to Sarah’s heart. Not only did she appeal in her magazine for donations to the school, but she sent both of her daughters there.

Among her charitable and philanthropic efforts during these Boston years, the Bunker Hill Monument was Sarah’s most ambitious. Learning in 1825 that group formed to commemorate the Battle of Bunker Hill had run out of money, Sarah asked each Ladys Book reader to send a dollar to help the cause. Male skeptics derided the idea that women could actually raise the needed funds, but Sarah shrugged off criticism. Ultimately, she joined the thousands who cheered the monuments dedication in 1843 a ceremony attended by President Tyler and made memorable by an oration delivered by another New Hampshire native, Daniel Webster. Eighteen years after placement of the original cornerstone, Sarah and her lady readers had ensured the projects completion.

While monitoring the Bunker Hill campaign, in 1833, Sarah also helped found the Seamen’s Aid Society. The first such organization of its kind, the Society was dedicated to improving economic conditions for men who spent their lives in the merchant marine, as well as to helping their families obtain financial and other assistance. Thanks to Sarah’s energy the Society grew into a multi-purpose institution that endures today.

When she left Boston in 1841 for Philadelphia, where the Ladys Book offices were located, she had thirteen years of managerial, editorial, and philanthropic experience. Yet her most productive years were ahead of her. From the early 1840s until her retirement in 1877, Sarah’s social conscience blossomed as her editorial influence expanded. Her commentary varied: she counseled on infant nutrition, recommended moderation in women’s dress (she tolerated the fashion plates for which the Ladys Book was famous, knowing that they promoted the magazine), and advocated equality for girls and women. Urging construction of playgrounds and advocating exercise for boys and girls, Sarah anticipated Progressive Era reforms by nearly six decades. As she praised female physicians, she ignored critics who said women were unsuited for the medical profession, criticizing those who warned that women doctors would cause economic ruin among their male counterparts. Not surprisingly, the Ladys Book warmly congratulated Elizabeth Blackwell in 1848 when she became the first American woman to earn a medical degree.

Sarah’s determination may be credited to her early education and the challenges she faced upon her husbands death, or she may have been naturally assertive at a time when the majority of American women remained silent at home. But unlike some of her contemporaries “notably Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, and Amelia Bloomer” feminists who sought dissolution of gender stereotypes and demanded full equal rights for women, Sarah remained a moderate. Promoting opportunities for women, she nevertheless valued their traditional roles. Her chief concern was that all women use common sense, and that each be given an education that would foster constructive use of her intelligence.

In 1855, she canvassed readers for money to preserve George Washington’s former home. Her campaign to make Mt. Vernon a nation shrine wore the veneer of sentimental patriotism common at the time, but Sarah believed that commemorating the first president was important. She hoped it would offer a symbol around which the nation might rally as it struggled with sectional disputes. In 1860 the Mt. Vernon Ladies Association purchased the Virginia property “ an accomplishment Sarah duly reported in the Ladys Book as a happy harbinger of faith.

But her most cherished victory was neither preservation of a building nor publication of a best-seller. Starting in 1846, Sarah had appealed to each president, asking him to announce an annual Thanksgiving observance. Abraham Lincolns decision to do so may have been motivated more by the notion that such a holiday presented a unifying device for a divided nation than by any conviction that Americans needed a day off. Whatever the reason, in 1863 Sarah’s efforts were rewarded by Lincoln’s Thanksgiving Day Proclamation (although it would be 1941 before Congress declared it a federal holiday).

While Sarah Josepha Hale cannot be placed in the same category as 19th century feminists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton or Susan B. Anthony, she nevertheless played a central role in promoting equality for women. Through the pages of Godey’s Ladys Book, which at its peak reached 150,000 subscribers, Sarah’s influence probably affected many more women than did the strident proselytizing of feminist reformers. Having faced the multiple demands of marriage and motherhood, she understood what subscribers wanted to find in the pages of the Ladys Book, and, continuing her life-long crusade to prove that women could accomplish whatever they attempted, she provided it.

When you think of an archive, what comes to mind? Do you usually picture a physical place with old and rare materials? While this is absolutely correct, modern technology has allowed for archives and preservation to be moved online and into digital archives.

Richards Free Library has a wonderful local history room that functions as our in-person archive, but I’m also developing our digital archives. There are many benefits to digitization and digital archives, and I hope that adding more materials to ours will serve as a benefit to our community.

Some of the exciting things about digital archives include easier access for homebound patrons and folks from out of town who are looking for Newport History. Digitizing also acts as preservation – physical materials deteriorate even with the best care, and are always at risk for loss or damage. Having a digital archive doesn’t mean the physical one goes away – it’s simply an additional way to access the materials!

So, what goes into digitizing?

While it can seem like a daunting process, all you really need is a scanner and a place to store the files. Some of the quickest materials to digitize are photographs, as they are single items and don’t require scanning multiple pages. However, with photographs you often have to be more aware of the resolution and color quality of your scanner than with text-based documents. Right now, RFL is still benefitting from the generous loan of a scanner from the New Hampshire State Library, and I am working my way through digitizing pictures from Newport’s past. The second part of digitizing is about resource description. Wherever your materials are ending up, they need to be easy to find. A description makes this possible. Photographs can be harder to describe than a document, especially if the photo has no description written on the back. Using things like subject headings and descriptive tags can help make photographs findable. We have some wonderful pictures of Newport’s past that I’m excited to share with our community! Stay tuned for updates on those projects.

We’re in the process of applying for a grant toget a scanner that RFL could have permanently, which would be a great asset to the archives. Digitizing is often slow and steady work, but permanent access to a scanner would allow for continuous additions to our digital archives.

As always, don’t be afraid to reach out to me if you have questions, a research request, or want to chat about Newport History!

Take care,

Juls

jsundberg@newport.lib.nh.us

You are more than welcome to make an appointment for cubby pickup!

Our Virtual Services are available 24/7!